Introduction

I have always been a big fan of all things by Korg, especially their line of hardware touchpad synthesizers, the Kaossilator and current Kaossilator 2. You just turn the little thing on, select a sound, touch the face and it makes music. I wanted to have something similar for my own phone. The result is not quite as fancy as the Korg version: I embed a single sound into my engine and there is no arpeggiator. However, with Android we can use multitouch to support playing chords and multiple events, something the Kaossilator cannot do. Also we are not limited to sample playback. We have the entire arsenal of Csound opcodes to generate sounds on the fly.

Making your own music app with Csound is extremely rewarding and exciting, and you do not have to understand every single aspect of Android app development to get started. You can copy one of the Csound examples or mash up a couple of those, and bootstrap yourself into native Android app development and keep learning as you go. This is how I got started and because I want to help you have as much fun as I did I released my code as open source. Now I am writing this article to take you through my process of development, step by step in detail. You can grab a copy of all the files used in this tutorial by cloning the open source github project at https://github.com/bredfern/PsychoFlute. You can also download a free copy from the Google Play shop to your Android device.

I. Creating the App Code

The Base Activity

To get started please refer to the .pdf document, Csound for Android[1] that comes with the Csound for Android[2] download and follow the setup instructions carefully.

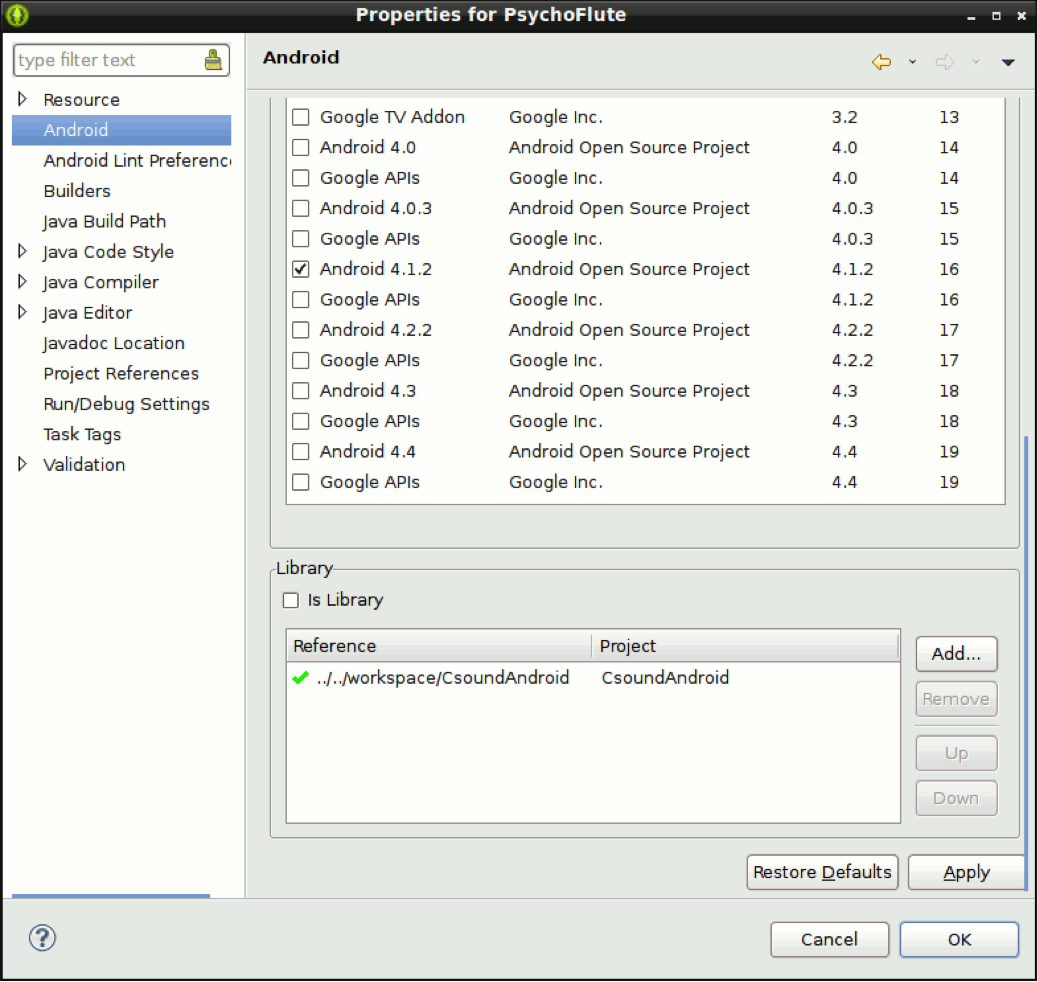

Figure 1. Eclipse IDE showing reference to CsoundAndroid Library.

You should now have a project setup with a reference to the CsoundAndroid library. You will not be able to do anything yet though. You need 3 additional files to help drive your app. To start, you will need to change your app to use a BaseCsoundActivity. Your BaseCsoundActivity is going to handle loading your .csd file from resources. It also handles the OnCreate and OnDestroy app methods. This extends the basic Android Activity class and your actual app code is going to extend this base code.

If you clone my project from GitHub you can get a shortcut by already having these files in place. However, if you want to create your own project from scratch I suggest you use the BaseCsoundActivity from the CsoundExamples that come with CsoundAndroid.

I will describe the code of the BaseCsoundActivity. To begin, we import all the classes we are going to use to load our .csd file and turn it into a string, as well as create our basic Csound object. The first thing we do is create the base Csound Object. We do not actually do anything with it here except create a new instance within the BaseCsoundActivity.

protected CsoundObj csoundObj = new CsoundObj();

Next we will override the basic Activity methods that any Android app needs to implement in order to run. We enable Csound message logging so that we can see what kind of messages we get from Csound. We also re-create an instance of the app from a saved instance if it is backgrounded. This is all pretty normal Android procedure you will find in any app code.

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

csoundObj.setMessageLoggingEnabled(true);

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

}

Next we need to override the onDestroy() method so that Android knows how to properly close the app. If we do not do this, Csound will continue to run even when the app is shut down and potentially cause problems for other apps. To be a good app citizen, we stop Csound when the app is destroyed.

@Override

protected void onDestroy() {

// TODO Auto-generated method stub

super.onDestroy();

csoundObj.stopCsound();

}

The next two methods grab our .csd resource file and turn it into a string. This is not too exciting, only just basic Java. Below we grab the resource file and then add it to a string called line. This will be passed to csound as the .csd file that is processed by the API. It might seem a bit convoluted but every resource in Android is stored within the binary APK file. The resource files then need to be processed into another state to become a string or other item to use within the app.

protected String getResourceFileAsString(int resId) {

StringBuilder str = new StringBuilder();

InputStream is = getResources().openRawResource(resId);

BufferedReader r = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(is));

String line;

try {

while ((line = r.readLine()) != null) {

str.append(line).append("\n");

}

} catch (IOException ios) {}

return str.toString();

}

The following utility method will create a temporary file on disk which is based on the name of our resource. It may seem convoluted, but Csound needs an actual .csd file which has to be temporarily generated to the disk.

protected File createTempFile(String csd) {

File f = null;

try {

f = File.createTempFile("temp", ".csd", this.getCacheDir());

FileOutputStream fos = new FileOutputStream(f);

fos.write(csd.getBytes());

fos.close();

} catch (IOException e) {

// TODO Auto-generated catch block

e.printStackTrace();

}

return f;

}

A final thing to notice is that you do not need to set the permission to read and write from the file system because we are only using the temp system.

The MainActivity

Now that our BaseCsoundActivity is setup, it is time to put together our MainActivity. You can actually call this activity whatever you want. In my app I only have one Activity deriving from my Base Activity so I call it MainActivity. This is where you are going to setup your view, capture your multitouch events, load your .csd resource and send your multi touch events to your Csound .csd synth. To begin with we are going to import the classes we need for the MainActivity.

import java.io.File; import java.util.Random; import com.magickhack.psychoflute.R; import android.graphics.Color; import android.os.Bundle; import android.view.MotionEvent; import android.view.View; import android.view.View.OnTouchListener; import com.csounds.CsoundObj; import com.csounds.CsoundObjCompletionListener; import com.csounds.valueCacheable.CsoundValueCacheable; import csnd6.CsoundMYFLTArray; import csnd6.controlChannelType;

We import some standard classes here: the Android View library, the touch classes to capture our events and the Csound classes to pass our events as arrays as well as the object completion listener to turn off Csound when interaction is complete and the value cacheable objects to cache our events before sending them to Csound. We also import the R or resource class for our own app so we can access the images and .csd file from the resources folders within the APK.

In addition to these features taken from the multitouch example, I added background color which changes depending upon how fast you move your fingers on the screen, as well as a background image that loads by default when the app starts up.

Next we are going to extend BaseCsoundActivity and implement the necessary interfaces within our MainActivity.

public class MainActivity extends BaseCsoundActivity implements CsoundObjCompletionListener, CsoundValueCacheable

After we create the main activity we will set up the multitouch view and activity variables.

public View multiTouchView; int touchIds[] = new int[4]; float touchX[] = new float[4]; float touchY[] = new float[4]; CsoundMYFLTArray touchXPtr[] = new CsoundMYFLTArray[4]; CsoundMYFLTArray touchYPtr[] = new CsoundMYFLTArray[4];

The view instantiation does not do anything but create a new instance of the the multitouch view class. Then we set up a series of arrays, shown below. The first array is an integer array that holds the IDs of the touch events. The next two arrays are float arrays that will store the raw X and Y data for the multitouch events. Finally we have the Csound float array types which will actually be used to send the data over the channel, translated from the touch id and raw data arrays. Notice the size of these arrays. I set them to 4 so I have a maximum of 4 finger multi touch. Set the number to 10 and you have 10 finger multitouch, but my instruments tend to get too loud with too many fingers so I intentionally limit mine to 4 fingers.

Before we get to the core of the app, we add two more small methods: the getTouchIdAssignment() method and the getTouchId(int touchId) method. These methods allow us to grab the touch id by number or to get a default item if the events are still in an initial state. If no id can be found it defaults to -1, which tells the engine no touch has occurred yet.

protected int getTouchIdAssignment() {

for(int i = 0; i < touchIds.length; i++) {

if(touchIds[i] == -1) {

return i;

}

}

return -1;

}

protected int getTouchId(int touchId) {

for(int i = 0; i < touchIds.length; i++) {

if(touchIds[i] == touchId) {

return i;

}

}

return -1;

}

Next we will dive into the core of the app. This is the onCreate method, which is called when the app is started up.

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

getWindow().setBackgroundDrawableResource(R.drawable.ic_pentagram);

csoundObj.enableAccelerometer(MainActivity.this);

for(int i = 0; i < touchIds.length; i++) {

touchIds[i] = -1;

touchX[i] = -1;

touchY[i] = -1;

}

multiTouchView = new View(this);

A few things happen above. First we are recreating the app from a saved state, in case it was backgrounded and returning to foreground active usage. Next we draw the background startup splash image so the user is not just confronted with a blank white screen. I am also enabling the accelerometer so I can pass that data along with the X and Y data to Csound. We do not need extra code to manually send the accelerometer data to our .csd because we have a built-in channel we can hook into from our .csd just by enabling the accelerometer here.

Next we set all touch IDs to -1 to initialize our arrays, so we know we are in an "untouched" state at launch, and finally we attach our multitouch view to the current active view. Then we are ready to start listening for multitouch events, and to do that we are going to use an anonymous OnTouchListener class, shown in the code below.

multiTouchView.setOnTouchListener(new OnTouchListener() {

public boolean onTouch(View v, MotionEvent event) {

// touch processing code goes here...

});

});

All of our multitouch processing code is going to live within this listener's method call. The call to setOnTouchListener() sets up an instance of the listener, and the listener's onTouch() method actually captures the touch activity so we can filter for a few different touch and click states. The inner loop is a boolean loop so at the end of processing input we simply return true to exit from the onTouch loop.

In order to handle both touchscreen and mouse based Android devices we are going to use a case statement to filter the actions based on a special action variable that combines both a generic motion event getAction() method call with an ACTION_MASK. I will also generate a random object to use to create a random color for my background later.

final int action = event.getAction() & MotionEvent.ACTION_MASK; Random rnd = new Random(); int color = Color.argb(255, rnd.nextInt(256), rnd.nextInt(256), rnd.nextInt(256));

From here we can use this action variable to switch our actions based on the kind of input events shown in the following code.

switch(action) {

case MotionEvent.ACTION_DOWN:

case MotionEvent.ACTION_POINTER_DOWN:

// handle touch and mouse click code here

break;

case MotionEvent.ACTION_MOVE:

// handle touch and mouse movement

break;

case MotionEvent.ACTION_POINTER_UP:

case MotionEvent.ACTION_UP:

// handle code touch touch off and mouse off

break;

}

The next chunk of code, shown below, is the largest amount of code. We are handling a combination of finger or mouse events touching or clicking the screen and then passing the X and Y coordinates to our .csd.

case MotionEvent.ACTION_DOWN:

case MotionEvent.ACTION_POINTER_DOWN:

for(int i = 0; i < event.getPointerCount(); i++) {

int pointerId = event.getPointerId(i);

int id = getTouchId(pointerId);

if(id == -1) {

id = getTouchIdAssignment();

if(id != -1) {

touchIds[id] = pointerId;

touchX[id] = event.getX(i) / multiTouchView.getWidth();

touchY[id] = 1 - (event.getY(i) / multiTouchView.getHeight());

if(touchXPtr[id] != null) {

touchXPtr[id].SetValue(0, touchX[id]);

touchYPtr[id].SetValue(0, touchY[id]);

csoundObj.sendScore(

String.format("i1.%d 0 -2 %d", id, id)

);

multiTouchView.setBackgroundColor((int) (id + id + color));

}

}

}

}

We loop through the pointer count of the event object. First we check for id == -1 so we know we are in a state of "raw touch". If a touch event was found, but ids have not yet been assigned, then we make the assignment and check again. If the assignment has worked the -1 should be replaced with the new touch id. We grab the X and Y coordinates for the event and then pass them to our running .csd. Then I change the background color of the view using a combination of my random color plus the X and Y variables that were passed to the .csd.

Next we are going to check for a movement event. In this case we do not pass the ids directly to the running .csd but store them in our id array instead, shown below.

case MotionEvent.ACTION_MOVE:

for(int i = 0; i < event.getPointerCount(); i++) {

int pointerId = event.getPointerId(i);

int id = getTouchId(pointerId);

if(id != -1) {

touchX[id] = event.getX(i) / multiTouchView.getWidth();

touchY[id] = 1 - (event.getY(i) / multiTouchView.getHeight());

}

}

We will check again to see that the id is not empty in this case and only add the X and Y to the touchX and touchY arrays. If we have touch ids set from the previous touch event, we need to have a touch event occur first before we can have movement. Finally when the finger or mouse is taken off the screen or in an unclicked state we go through the final case statement logic shown in the code below.

What happens here is that we detect that the interaction is over. If the pointer id is not -1 then we send any events that need to go to Csound before we stop playing. Then I pass the id variables and mix them with the random color to switch the background color according to the event.

case MotionEvent.ACTION_POINTER_UP:

case MotionEvent.ACTION_UP:

int activePointerIndex = event.getActionIndex();

int pointerId = event.getPointerId(activePointerIndex);

int id = getTouchId(pointerId);

if(id != -1) {

touchIds[id] = -1;

csoundObj.sendScore(String.format("i-1.%d 0 0 %d", id, id));

multiTouchView.setBackgroundColor((int) (id + id + color));

}

Below, I set the background color again, just using the random color in order to give a strobing color effect.

multiTouchView.setBackgroundColor(color);

After we escape from the touch event loop we have to do a few more important steps. Below, we set the actual content view to the multitouch view, before we set up the class and create an instance of the object. Here we actually load it into the running view. Then we load the Csound resource and turn it into a temp file to process it into a string. Then we add our cached values and actually start Csound running. Now we just have a couple of helper methods to add to the Java part of our app and it is done.

setContentView(multiTouchView); String csd = getResourceFileAsString(R.raw.multitouch_xy); File f = createTempFile(csd); csoundObj.addValueCacheable(this); csoundObj.startCsound(f);

For this application this method shown below is left empty because the mouse/fingers off part of the event loop already handles this state so we do not need to stop Csound from running here as we might with other kinds of apps. Next we have our methods used for the Csound value cache.

public void csoundObjComplete(CsoundObj csoundObj) {}

The methods below map the input of the touch ids to the Csound control channels, and then handle updating those values. The update from method is blank because we are only sending to Csound on the channel. Nothing is being returned back from Csound to the app.

public void setup(CsoundObj csoundObj) {

for(int i = 0; i < touchIds.length; i++) {

touchXPtr[i] = csoundObj.getInputChannelPtr(

String.format("touch.%d.x", i),

controlChannelType.CSOUND_CONTROL_CHANNEL

);

touchYPtr[i] = csoundObj.getInputChannelPtr(

String.format("touch.%d.y", i),

controlChannelType.CSOUND_CONTROL_CHANNEL

);

}

}

public void updateValuesToCsound() {

for(int i = 0; i < touchX.length; i++) {

touchXPtr[i].SetValue(0, touchX[i]);

touchYPtr[i].SetValue(0, touchY[i]);

}

}

public void updateValuesFromCsound() {}

We have one final cleanup method which frees up the channels that were previously cached for all of the touch channels.

public void cleanup() {

for(int i = 0; i < touchIds.length; i++) {

touchXPtr[i].Clear();

touchXPtr[i] = null;

touchYPtr[i].Clear();

touchYPtr[i] = null;

}

}

That is it for the Java portion of our app. That is quite a lot going on. We could try to add more but to keep things lean and mean we can change the background color without evening having to run a separate thread because Android is handling that property change behind the scenes in an elegant way for us.

II. Developing the Csound Code

CSD Setup

So now that we have our app done, we need a Csound file to receive our channel messages. The wgflute opcode, being one of my favorites, is a natural one I would choose to receive messages from this app. I used the multitouch .csd example as the basis of my app but then made a bunch of modifications on top of switching the opcode from an oscillator to the physical model. First off, I used the same settings as the example for my audio output.

-o dac -d -b512 -B2048

We are setting up basic audio output to the DAC and then setting a buffer size of 512 and 2048 for software and hardware buffers sizes, giving clean audio output. Next we will setup the Csound header. This is also a standard setting for stereo output.

nchnls=2 0dbfs=1 ksmps=32 sr = 44100 ga1 init 0

We are using a standard sample rate and use 0dbfs for volume control. Note the ga1 variable. We will use this variable to pass the wgflute opcode output into a moogladder filter opcode.

The Opcodes

The largest chunk of our code is used by the flute instrument. Here we map the channels to the control parameters. As above, we could do more, like mapping to the filter to control it from channels, but for now the filter is just there to add grit to the flute sound and has a set resonance and cutoff. Here is the final code for the opcode instrument.

instr 1 itie tival i_instanceNum = p4 S_xName sprintf "touch.%d.x", i_instanceNum S_yName sprintf "touch.%d.y", i_instanceNum kx chnget S_xName ky chnget S_yName kaccelX chnget "accelerometerX" kaccelY chnget "accelerometerY" kenv linsegr 0, .0001, 1, .1, 1, .25, 0 kamp = .5 * kenv kfreq = kx*100 kjet = rnd(900) + ky + kaccelY * 0.001 iatt = 0.1 idetk = 0.1 kngain = 0.005 kvibf = rnd(10000) + ky + kaccelX * 0.001 kvamp = 0.00005 ifn = 1 asig wgflute kamp, kfreq, kjet, iatt, idetk, kngain, kvibf, kvamp, ifn ga1 = ga1 + asig endin

We grab both the X and Y multitouch channels and the accelerometer channels and combine those values with randomly generated values to create a semi-controlled, semi-random instrument. Then we pass this to the simple moogladder filter to add some analog style grit to the flute sound before it goes to audio output.

instr 2 kcutoff = 6000 kresonance = .2 a1 moogladder ga1, kcutoff, kresonance outs a1, a1 ga1 = 0 endin

We reset the ga1 variable back to 0 after output. We have a single function table for the wgflute opcode, and then we setup a very simple score to cause the instrument to play indefinitely.

f1 0 16384 10 1 i2 0 360000

That is the complete process for the .csd portion of the code. Now we can build our touchpad synth app and share it with the world, or even keep it to yourself as a musical "secret weapon" for live performance.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the talented geniuses who created the Csound Android Native Library. The development of this library represents a major achievement. Software that once required a mainframe level machine to run now runs on even modest inexpensive ubiquitous Android hardware.

References

[1] Victor Lazzarini, Steven Yi and Martin O'Shea, "Csound for Android," in "csound-android." [Online]. Available: http://sourceforge.net/projects/csound/. [Accessed January 15, 2014].

[2] Victor Lazzarini, Steven Yi, et. al., "csound-android." [Online]. Available: http://sourceforge.net/projects/csound/. [Accessed January 15, 2014].

Additional Links

Eclipse IDE. [Online]. Available: http://www.eclipse.org/downloads/. [Accessed January 15, 2014].

Korg. "Kaossilator 2." [Online] Available: http://www.korg.com/kaossilator2. [Accessed January 15, 2014].

Steven Yi and Victor Lazzarini, "Csound for Android." [Online]. Available: http://lac.linuxaudio.org/2012/papers/20.pdf. [Accessed January 15, 2014].

Victor Lazzarini, Steven Yi, et. al., "The Mobile Csound Platform," from ICMC2012_Non-Cochlear Sound, Ljubljana, Slovenia, September 9-14, 2012. [Online]. Available: http://eprints.nuim.ie/4163/1/mobile-csound-platform.pdf. [Accessed January 15, 2014].